-

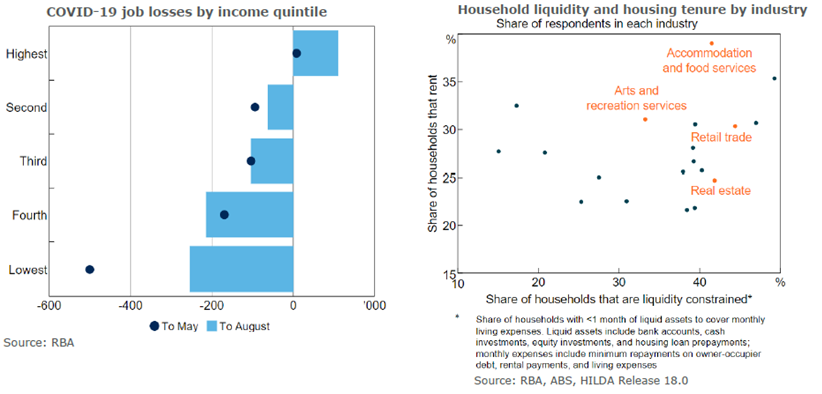

The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions has been uneven, with low-income workers, young people, arts and recreation workers and hospitality workers disproportionately affected by loss of employment and income. On top of this, a relatively high proportion of people in these cohorts rent.

This concentration of COVID-19 related job losses in low-income brackets is likely to increase the number of households at risk of needing social housing or financial assistance for rent. And while approvals for social housing developments have risen since the beginning of the pandemic downturn, they are still at very low levels compared to the long-term average.

"Sadly, the underlying demand for social housing was already far exceeding supply.”

{CF_IMAGE}

Sadly, the underlying demand for social housing was already far exceeding supply. In 2018-19:

- 797,000 Australians were in social housing programs;

- 1.29 million income units received Commonwealth Rental Assistance (CRA); and

- 91,800 households received private rental assistance.

Of households with newly allocated public housing in 2018-19, 36.1 per cent had waited a year or more to be allocated social housing and a further 15.7 per cent waited 6-12 months. This suggests an undersupply of social housing.

In 2016, the estimated shortfall of around 431,000 social housing dwellings was forecast to grow to 727,300 by 2036. This translated to a need for around 36,000 new dwellings per year.

{CF_INFOGRAM}

Economic and social benefits

Increased investment in social and affordable housing has long-term social and economic benefits in the recovery from the pandemic.

First, increasing the stock of social housing will reduce some of the accommodation shortfall for people experiencing or at-risk of homelessness. This is particularly important given the pandemic’s obvious impact on low-income jobs.

Reducing homelessness through social housing also supports public health. It is estimated that of homeless people in Australia, 73 per cent of men and 84 per cent of women have at least one mental health disorder. Productivity Commission research suggests appropriate housing contributes to both prevention of and recovery from mental health disorders. Educational attainment levels, social inclusion and protection from domestic violence all improve with social housing investment.

Increased social housing investment would offer employment opportunities in construction and would have a large multiplier for economic activity. This counter-cyclical investment approach would help smooth construction activity and investment through the business cycle. It is estimated an average of 80 construction jobs and 30 ongoing jobs are created for every 100 units of new public housing.

Commonwealth stimulus less than GFC

The Australian Federal Budget enabled the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation to issue an additional $A1 billion worth of bonds to attract institutional investment to increase the supply of affordable housing. While this support is a step in the right direction, the overall level of support remains low compared with previous crises.

During the global financial crisis (GFC), the federal government’s Social Housing Initiative allocated $A5.6 billion for new construction and repairs and maintenance across all states and territories. This saw annual work done quadruple in two years. 19,700 new dwellings were built, and repairs and maintenance ensured a further 12,000 remained habitable. People experiencing homelessness, people with a disability and elderly people were the main beneficiaries.

{CF_INFOGRAM}

State support more direct

A number of state governments have made budget commitments for social housing this year. These will have two effects: stimulation of construction activity and preparation for elevated demand.

In contrast to the federal government, policies announced so far this year by state and territory governments are more direct. These are summarised below and do not include one-off payments in response to COVID-19, such as rental grants for households in rental arrears, one-off rebates for utility bills and one-off payments for workers with COVID-19 or awaiting test results.

Spending is highest in Victoria, by a large margin, with $A5.3 billion earmarked for social housing in the latest budget.

{CF_INFOGRAM}

Financial assistance as an alternative

Commonwealth rental assistance (CRA) is one alternative to social housing for vulnerable households. However, CRA does not fully shield households from rental stress, which is defined as spending more than 30 per cent of total take-home income on rent for lower income households. Some research suggests financial assistance for housing can be ineffective when rental markets are unregulated and vacancies are low.

However, CRA does go some way to alleviating rental stress. After receiving the CRA payment, 40.5 per cent of recipients in 2018-19 were no longer in rental stress, but 59.5 per cent remained in rental stress. In particular, almost three quarters of CRA recipients under 24 years of age remained in rental stress.

{CF_INFOGRAM}

Throughout the pandemic, workers under 25 years of age have been more likely to lose employment. Young people may be more vulnerable to homelessness or rental stress than other age groups, because they are less likely to have sufficient savings or superannuation accessible under the early-release program.

The historical rate of rental stress for people under 25 receiving the CRA suggests social housing may be more effective than financial assistance for this cohort.

{CF_INFOGRAM}

ANZ’s $A10 billion commitment to support access to housing

- written by Caryn Kakas

In responding to the pandemic, governments at all levels were confronted with the challenge of being able to provide access to stable accommodation for everyone. The need for people to be safe in place highlighted the fundamental importance of housing as a basic need for all people in our community. The economic and social pressures that resulted from COVID-19 have highlighted the stark reality of the gaps in the housing market (including the ability to access social and affordable housing). The economic fallout has increased the demand for housing, services and supports to respond to both the pandemic and its aftermath.

Is there a role for financial institutions to play?

ANZ believes the bank can play a role in helping improve the availability and affordability of housing, including support for innovative housing delivery models across the private, public and not-for-profit sectors.

At the end of 2018 ANZ committed to fund and facilitate $A1 billion of investment by 2023 to deliver around 3,200 more affordable, secure and sustainable homes to buy and rent in Australia. In 2020, the bank has already exceeded this target. In addition to $A1.02 billion of investment in Australia, ANZ has also funded and facilitated around $NZ1.35 billion to support the delivery of social and sustainable housing across New Zealand.

Although 2020 has been a more difficult year than most, ANZ continued to build its housing supply pipeline in direct partnership with new and existing clients to support new supply into the market.

In 2020 the bank has:

- Jointly arranged two additional bond issuances for the Commonwealth’s National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation including the largest social bond for housing in Australia ($A562 million);

- arranged bonds for Kāinga Ora (Housing New Zealand Corporation) to support the delivery of more social and sustainable housing (jointly $NZ1 billion; solely $NZ300 million);

- supported the first Assemble Model, designed to bridge the gap between renting and owning a home to market;

- invested in the development of a Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) pipeline; and

- helped build the case for institutional investment in long-term rental housing through the backing of a range of ‘build-to-hold’ projects.

The need for housing is an essential ingredient that ensures that communities are able to thrive. With that in mind, ANZ's work has only just begun. The bank has set a new commitment to fund and facilitate $A10 billion of investment by 2030 to deliver more affordable, accessible and sustainable homes to buy and rent in Australia and New Zealand. Because access to housing is the best way to ensure equality of social and economic opportunities for everyone in our community.

Caryn Kakas is Head of Housing Strategy at ANZ

Adelaide Timbrell is Economist, Felicity Emmett is Senior Economist and Catherine Birch is Senior Economist at ANZ

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

-

-

-

-

anzcomau:Bluenotes/Housing,anzcomau:Bluenotes/global-economy,anzcomau:Bluenotes/COVID-19

Social housing: helping the vulnerable and the economy

2020-12-04

/content/dam/anzcomau/bluenotes/images/articles/2020/November/TimbrellSocialHousing_banner.jpg

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Social bonds are due to emerge as the fastest growing segment of the sustainable debt market in 2020.

17 July 2020 -

Home ownership has changed dramatically, so what are the social and economic forces at play? We present two insightful perspectives.

24 April 2018