-

In the wake of the dramatic reconstruction of the board of Australian life insurance and financial advice giant AMP following disastrous revelations in the Royal Commission, two particularly specious arguments appeared in the analysis.

Because the three directors in focus were women, including chair Catherine Brenner, too many (sadly influential) commentators ran an argument along the lines of ‘was she really qualified for the job or promoted beyond her skills because of her gender?’

"Evidence shows all male boards have demonstrated a far greater propensity to fail in absolute terms.”

The second specious line argues there is no evidence gender - or indeed broader diversity – on boards contributes to shareholder value creation.

Both are wrong. The former logically, the latter contradicted by actual research.

Consider the former: from a case study of one, the proponents conclude it was the expedient installation of more women on the board which led to the poor behaviour and ultimate crisis.

However, even a cursory glance at the last half a century of corporate failure would demonstrate in the overwhelming majority of cases the chairs and boards of these companies were almost exclusively male. Ipso facto, we should avoid all male boards; that’s the counterfactual scenario.

Of course, it is also the case the arrival of at least some women on boards is a relatively recent phenomenon so the historical data are skewed. But that doesn’t obscure the fact that the evidence shows all male boards have demonstrated a far greater propensity to fail - in absolute terms.

What none of these cases demonstrate is any causative link between the gender of board members and the value the board oversees the creation or destruction of.

That brings us to the second fallacious argument: there is no evidence. Wrong. There is. And it is growing.

Growing

One of the pieces of work most widely cited by major investors is a report by Institutional Shareholder Services and the McKinsey Global Institute.

Using the research, State Street, one of the world’s largest investors, found an average 36.4 per cent increase in return on equity for companies with strong female leadership. Average price to book ratios in such companies was 1.8 compared with 1.6 where such leadership was absent.

McKinsey summarised the last decade of research earlier this year to address the dissent.

“Of course, a correlation does not prove causation, and some academics have disputed what they regard as the intuitive appeal of a link between diversity and performance,” the institute noted.

“Nevertheless, a growing body of research by McKinsey continues to strengthen that link. Our 2018 Delivering through diversity study of more than 1,000 companies in 12 countries found a correlation between diversity at the executive level and not just profitability but also value creation.”

“Those companies in the top quartile for gender diversity were 27 per cent more likely to outperform their national industry average in terms of economic profit - a measure of a company’s ability to create value exceeding its capital cost - than were bottom-quartile companies.”

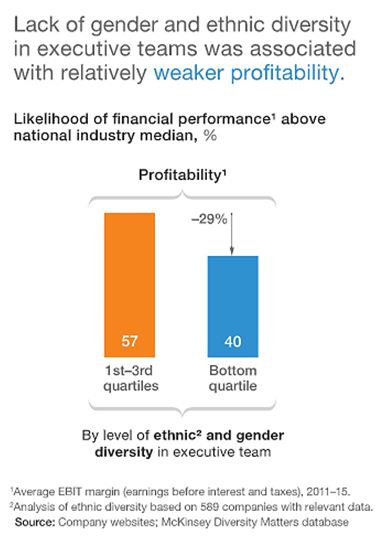

“There was also a penalty for lack of diversity more broadly. Companies in the bottom quartile on both gender and ethnic diversity were least likely to record higher profits than the national industry average.”

{CF_IMAGE}

The Boston Consulting Group looked more closely at one of the critical factors for companies facing disruption, the ability to innovate. Once again, diversity delivered a measurable advantage.

BCG reported “increasing the diversity of leadership teams leads to more and better innovation and improved financial performance. In both developing and developed economies, companies with above-average diversity on their leadership teams report a greater payoff from innovation and higher EBIT margins”.

The report, How diverse leadership teams boost innovation, found “companies that reported above-average diversity on their management teams also reported innovation revenue that was 19 percentage points higher than that of companies with below-average leadership diversity—45 per cent of total revenue versus just 26 per cent”.

{CF_IMAGE}

Compelling

While the accumulating data are compelling there is still the issue of basing appointments on merit and not some other factor such as quotas. This is a broader challenge as it is by no means simple to define ‘merit’ in a board context.

Still one of the best texts on the subject comes from Australian company director and board reviewer Colin Carter in his book Back to the drawing board.

Carter’s central point is boards are social, private entities whose success or failure is not readily measured on some ‘dashboard’. Because of this essential nature, Carter argued expectations of boards are too high.

Ultimately, the measure of a functioning board is they ‘can smell the smoke under the door’. From both his time reviewing boards and being on them, he argued it is even less realistic to be able to link specific directors to specific outcomes in any normal course of events.

"We know boards do something but we can't measure it," he once told me. "Boards are accountable for letting festering problems run too long but they should not be expected to know what's going on down in the engine room.”

“But if the signs are there, the market knows, everyone knows, then they are accountable. It is a question of whether their smoke detectors are working.”

That was more than a decade ago but it still holds true today. The discussion was at a time when the board and senior management of a major bank had imploded as a result of a rogue-trading scandal which saw both the chairman and CEO depart.

Interestingly, the primary agitator at the time was the only female director on the board.

The smoke

So what should be considered when discussing ‘merit’?

The evidence tells us there should be diversity but what kind? Gender? National? Industry? The essence here is the ability, in Carter’s words, to “smell the smoke”.

As the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has made clear in responses to malfunctions over more than a decade, it is essential to avoid group think, to ask questions, to bring a different perspective.

While diversity is valuable for many reasons – typically a company’s customer base is pretty diverse, for one – it is this capacity to question the received wisdom which is vital.

Lack of merit is hardly gender specific. At a recent forum of major shareholders I attended in Tokyo on the subject of the value of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria, one panel was quizzed on whether the drive to install more female directors when the pool was still small might result in some less-than-effective directors being appointed; their presence based more on their network and demography than their skills.

One – male – chief investment officer of an enormous pension fund replied he didn’t “spend much time worrying about that given it’s been the case with so many male directors for so long”.

One of the most salutary lessons, however, is from a ‘fantasy board’ that really did exist.

This board had everything, every box was ticked. Its directors were global figures; Nobel Prize winners; industry champions; the racial and gender diversity was exemplary. It belonged to Enron.

Andrew Cornell is managing editor at bluenotes

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

anzcomau:Bluenotes/workplace-diversity,anzcomau:Bluenotes/Leadership-and-Management

Diversity, boards & the specious theories of threatened species

2018-05-30

/content/dam/anzcomau/bluenotes/images/articles/2018/May/CornellBoards_banner.jpg

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Big investors back diversity and sustainability – and they’re right to, results suggest.

1 November 2017 -

The lack of diversity in Australian boardrooms means business is not making the most of the talent the country has to offer, according to Australia's Race Discrimination Commissioner.

20 December 2016