-

To celebrate International Women’s Day, all week bluenotes will be guest edited by respected journalist and author Catherine Fox. We’ll be publishing content on women, their experience in the workplace and the future of equality. We hope you enjoy it.

There are days I wish I was back at University, going from lecture to lecture, learning about everything from discrete mathematics to obscure facts about quantum physics and supercomputing.

So when I was recently asked to join the advisory board for the Melbourne University School of Computing & Information Systems, there was always going to be one answer.

At my first board meeting the attendees were a mix of faculty, corporates, governments and start-ups, with the major agenda item for this month’s meeting relating to trends in emerging technology.

"56 per cent of women in technology companies leave their organizations at the mid-level point (10-20 years) of their careers."

During the course of our discussion, I came across some interesting statistics:

• Education is one of Victoria’s biggest exports, generating $A6.5 billion last year and supporting 30,000 jobs (not relevant to the topic I know but fascinating nonetheless);

• Melbourne University graduate intake in Computer Science related subjects has doubled since 2015; and

• 2016 saw a 13 per cent higher enrolment in computer science than 2015.

But two stood out:

• Most Computer Science departments nationally have around 11 per cent female enrolments; and

• At Melbourne University of 230 computer science students just 33 are female.

That final statistic provoked much discussion: why are female enrolments in computer science so low and seemingly on the decline? This is reflective of what we’re seeing in IT industry – females are underrepresented in technology roles.

At ANZ I have been the sponsor an initiative called iCreate, which aims to educate women across the organisation on the opportunities within technology. We have rolled this program out across ANZ, schools and the indigenous community in the hope of getting more women interested in pursuing a technology career.

There are many such programs being run by corporates and individuals globally but none of them seem to be having any tangible or measurable impact at scale. So the question still remains – why are there so few women in technology?

What is the data telling us?

McKinsey tells us women in the tech industry hold only 37 per cent of entry-level jobs – much lower than the 47 per cent of women who on average are offered entry-level positions in other industries. Women in tech hold 30 per cent of the managerial positions, 25 per cent of the senior manager or director roles, 20 per cent of the vice president titles, and just 15 per cent of roles in the c-suite.

Research from Girls Who Code and Fortune magazine tell us just 18 per cent of computer science graduates are women and while 74 per cent of girls in middle school express interest in STEM subjects, just 0.4 per cent of high-school girls actually choose computer science as a college major.

Teh female 'quit rate' in technology exceeds other science and engineering fields; 56 per cent of women in technology companies leave their organisations at the mid-level point (10 to 20 years) in their careers.

Fifty seven per cent of the professional occupations were held by women in the workforce, but 25 per cent of the computing workforce were women in 2011.

At Stanford University in 2011 56 per cent of test-takers were female; 46 per cent of calculus test-takers were female, and only 19 per cent of computer science test-takers were female.

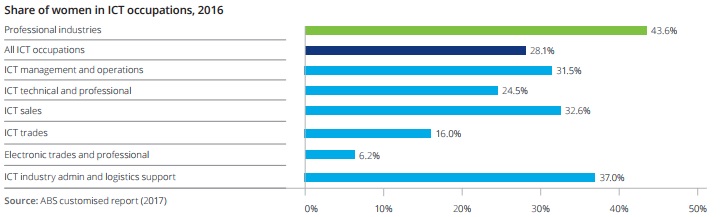

The Digital Pulse 2017 from the Australian Computer Society has data showing of all ICT technical professions only 24 per cent of the workforce are female.

{CF_IMAGE}

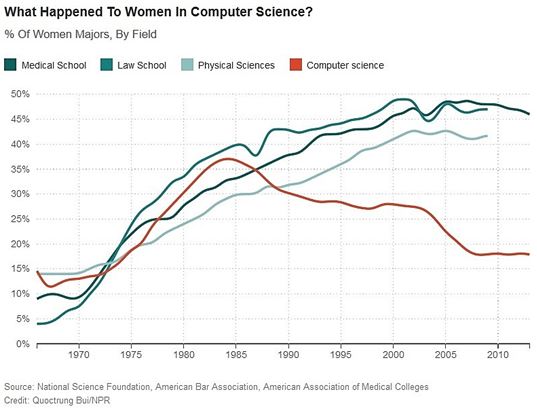

During my research I came across this graph which shows the percentage of women in medicine, law, physics and computer science between 1970 and 2013.

{CF_IMAGE}

The question which clearly comes to mind is - what happened around 1983 to start this sharp decline in computer science?

Well, the personal computer started to become more mainstream – in 1982, the Commodore 64 was the best-selling PC of all time. I had one, learned to program in basic on it and wrote my very first game using basic and sprites (unfortunately there wasn’t an app store for me sell it on).

Shortly after the Commodore 64, the IBM XT PC was released and as prices dropped, marketers seemed to target these devices at boys and young men. It could be plausible to state young men when attending university had more exposure to computers and this advantage may have caused an uneven playing field, leaving women discouraged and not wanting to compete. (It’s an interesting and hopefully coincidental sidebar the decline coincided with the first Revenge of the Nerds movie, caricaturing anyone interested in computing as male and geeky).

Why have we not been able to reverse this trend?

I don’t think there is one simple answer and I don't pretend to know the solution but I have a belief there are three main causes contributing to our current predicament:

• There is a supply problem - we are not getting enough females interested in the computer science related disciplines.

• There is a gender bias/cultural issue.

• There is a retention issue - females are leaving the IT disciplines at a faster rate than new ones are coming in.

The supply problem

If I go back to my first Melbourne University advisory board meeting, the comment was made that there are 2000 applicants for Medicine yet they only offer 150 spots. It begs the question - what makes the medical field so much more attractive?

Pay

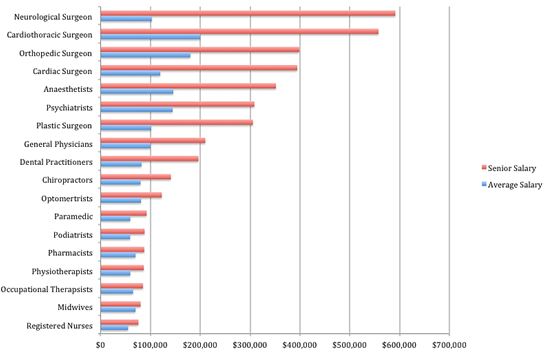

One hypothesis is the pay is high. Assuming you go on to specialise in areas like neuroscience, anaesthesiology and orthopaedics then this is generally true.

However the vast majority of students doing medicine will follow a path to become a general practitioner. The research data shows the average GP salary in Australia is around $A120,000 with a senior practitioner earning between $A250,000 and $A300,000.

{CF_IMAGE}

The salaries for people in the information technology field have been increasing rapidly. Programmers in fields like Java, IOS and Android are in huge demand and masters in these fields are earning well over the average GP salary.

Other less-technical disciplines such as agile coaches and scrummasters are in high demand and fall into the same high-earning brackets. Based on current conditions I would argue the average programmer is now earning more than the average GP.

Additionally, many of the engineers working for me also have their own side businesses. They have developed apps or their own start-ups which earn supplemental income.

Do we need to educate students more about the financial benefits of pursuing a career in information technology?

There are also many other non-financial benefits often not understood.

• Transferable skills and international opportunities

The information technology field provides skills which are highly transferable. The trade allows you to work in any country in the world without retraining or recertifying, which is not the case with fields like medicine or law. Java in Australia is the same as Java in Russia or the United Kingdom.

• Flexible Working

Informational technology fields are well suited to flexible working. Working from home or telecommuting and job sharing is well suited to disciplines like programming, design, CX/UX. There are also many opportunities for part-time work and job sharing working two to three days per week or during school hours only.

• Misinformation and misunderstanding of IT fields

The stereotypical portrayal of information technology workers is a geeky/nerdy looking male with a big laptop and ego to match. Or a hipster with jeans, t-shirt, wearing a large set of beats headphones attached to his MacBook pro.

The reality is so far from this, yet TV and media continue to push this view onto society.

Granted, I do have some of the exact stereotypes I mentioned above working for me. And in some disciplines like hard core programming with full stack engineers, the stereotype is unfortunately more often than not true.

What I feel is we are not educating students about is the diversity of the information technology field. There are roles within it which suit all personality types:

• Highly creative roles in user experience design;

• Innovative big idea thinkers doing CX and design thinking;

• Detailed oriented number crunchers running project and project plans;

• Architects who need to think about the end to end big picture;

• Agile coaches who study team and human behaviour and coach teams to get the best out of them;

• Business engagement/relationship management roles which act as a bridge between business ideas and the technology implementing them; and

• Communication specialist which work with business and technology teams to keep large number of people on message using social media, video, email and live chats.

This is just a fraction of the subset of roles and most of them listed above do not require hard-core engineering or STEM-related background.

Challenge

I challenge the notion great programmers must be great scientists or mathematicians. Part of the misinformation is we are focusing so much on getting women into STEM subjects.

In the US in 2009, women earned 57 per cent of all undergraduate degrees, 52 per cent of all math and science degrees, 59 per cent of the undergraduate degrees in biology and 42 per cent of mathematics degrees. Yet they only earn 18 per cent of all computer and information-science undergraduate degrees.

From personal experience, mathematics was never my key strength. Certainly not for all disciplines within the field. I was terrible at calculus for example - I just never got it. I was average at statistics and discrete mathematics and above average at algebra and logic. But this never held me back in computer science.

Despite not having a very strong engineering-based mathematics background, the creativity of problem solving in programming was something which came naturally to me and I passed all my programming related computer science subjects with high distinctions. I did not need to be a maths genius to be a good programmer.

The point being is I don’t believe we should be drumming a message to students like 'if you’re not great at STEM subjects, you can’t take on information technology related degrees at university'. The discipline of information technology has grown to encompass much more than science and engineering.

It includes social, psychological and human elements of analysis and design which are now more important than ever, as customer experience becomes a differentiator for successful businesses. We need to bring an 'A' in to STEM which is around the art of engineering solutions for human, social and physiological consumption.

We need programs at schools which educate students on the diversity of information technology related roles and the fantastic financial rewards and freedom which can come with making that choice.

Plase don’t misinterpret the message I am giving above - I am not of the belief we shouldn’t encourage more females to take an interest in STEM subjects. We absolutely should. I am just saying it’s not a mandatory pre-requisite to many of the fields which now fall within the scope of information technology field of work.

Parental influence

I decided to add parental influence to the topic of supply problem after a recent conversation with the Maria Markman (The Branch Chair in Victoria of the Australian Computer Society). Markman has a deep science and technology background.

During our discussion about why she was interested in computer science it became apparent a huge driving influence was her father who was convinced information technology knowledge was going to be a skill which would be needed in the future.

Markman was raised in Moscow and I was curious to see if cultural differences were impacting the pipeline. It turns out this does seem to be the case - according to UNESCO, 41 per cent of Russians in scientific research are women.

Further reading confirmed what I suspected. Russian parents have a strong influence on their children’s interest in STEM subjects. There does not appear to be social stigma against doing well in STEM subjects like it seems to be the case in many Western countries.

There also appears to be a much higher percentage of Russian female schoolteachers which encourage STEM subjects and act as role models.

This pattern seems to be similar in countries like India and Israel. I spoke to some of my female Indian engineers who shared stories of parental encouragement and lack of social stigma associated with excelling in STEM subjects.

We spend a lot of time looking to influence young women to be interested in STEM. Programs like Go Girl, Go for IT, Rail Girls and Girls Who Code do a great job of this. But I think it’s time we also started to focus on influencing and educating parents.

The role of our teachers

The more I researched the role of parents a number of my conversations revealed a significant number of the daughters of parent I spoke to had their career choices influenced by the teachers and schools they were at. Many of the career councillors were steering young women towards traditional careers in law, medicine and finance. Why?

I decided to find out so visited the career councillor at my daughter’s school. The short summary of my findings is lack of knowledge themselves and therefore confidence to talk to our young women about career options in the IT field.

I also don’t see the schools doing enough around IT-related subjects which link emerging trends in society to technology. Think about the impacts artificial intelligence combined with big data analysis is having on our lives.

Services like Uber, Google Home, Alexa would not be possible. Driverless car technology would not be a reality. These merging technology fields will change our lives in the future more than any other single factor yet they are not even being discussed at school.

The gender bias/cultural issue

Given the fact there are more male software engineers active in the workplace it's not surprising many software-development based workplaces feel gender biased and as such are full of symbols enforcing a male-dominated culture.

The heroes of Silicon Valley are often referred to as 'code warriors' or 'ninja coders'. They 'crush code' and build 'killer apps'.

Just listen to the language. It's unconscious but creates a culture which feels aggressive and very male.

Next time you are in an office which runs agile delivery, observe the scrum walls. Look at the Avatars typically stuck to story cards. Notice anything? I guarantee you will find them full of super heroes and characters from Game of Thrones.

One of the very important roles within an agile delivery squad is called a scrum master.

Once again none of these symbols come from a negative place with any intended bias, but they unintentionally create unconscious bias.

What you then often see is over compensation. I have been to a number of Women In IT events full of pink - unicorns and rainbows everywhere, complete with pink champagne. Fortunately, this over compensation seems to be on the decline, as employers come to realize how unsuccessful this strategy really is.

Recruitment bias

When we recruit for software engineers the fact, whether we like it or not, is there are 76 per cent more male candidates qualified in the software engineering talent pool - data from Seek and LinkedIn confirm this.

Now put yourself in the shoes of recruitment professional. Your income is dependant on you placing qualified candidates into roles. You are also in a highly completive industry competing against other recruiters who have the exact same goal. Company X advertises it needs a full stack engineer.

As a recruiter you can probably at most put three candidates in front of Company X. Now put yourself back in the shoes of the recruiter whose livelihood depends on Company X hiring a candidate from them.

What would you do? Would you risk losing the placement by taking the extra time to try finding a qualified female candidate out of the small pool of 25 per cent? Or do you play the odds and revert to the large 75 per cent pool of males?

Statistics and human nature lead to a bias that’s ends up feeding a never-ending cycle.

Having spent a significant amount of time building a new team over the past 18 months, the other observation I have is there is unconscious bias in how job descriptions are written.

I used Gender Decoder to check some of our recent job adverts and I had the following response returned: “This job ad uses more words that are stereotypically masculine than words that are stereotypically feminine. It risks putting women off applying, but will probably encourage men to apply.”

ANZ has started to ensure for every role we hire we have at least one female on the interview panel. Since doing this we have noticed less unconscious bias occurring during interviews.

I had one of my male team members comment recently after an interview he was surprised to realise he was unconsciously biased. He realised some of the questions he was asking and the way he interpreted the answers were generating bias and his interpretation of the answers were completely different to the female panellist with him.

The retention issue

Women’s resignation rate in technology exceeds that in other science and engineering fields; why? Workplace discrimination is still happening.

Working for a progressive organisation like ANZ which takes workplace equality very seriously and is part of our everyday values, I thought discrimination was not something still happening and could not be contribution to the problem.

I recently discovered how wrong I was. At a recent leadership offsite three of our senior female leaders shared their experiences over the past five years. Their stories shocked me. Listening to their stories and seeing the faces of my male colleagues around the room as the realisation of what is still happening right under our noses had a profound impact.

Could this kind of discrimination be a contributor to the high degree of mid-career exits? If women are self-selecting out because of the environment it by nature will continue to make the environments more masculine.

The workplace environment leading to exits leading to a less welcoming environment (unintentionally) may be causing a negative spiral.

There is still so much to do to educate leaders about the kind of gender bias and discrimination still happening. It takes brave women to stand up and tell these stories to get the message out. It will also take brave leadership to listen and then act.

Glass ceilings

There are a number of factors at play here, but at its core, this issue relates to the perceived glass ceiling within technology around leadership positons. Currently, females make up only 11 per cent of all executive positions in Silicon Valley at a time where girls in school are looking for role models akin to the Bill Gates of the world.

The premier annual technology gathering CES with over 200,000 attendees kicked off in Las Vegas in January 2018. It was widely criticised for not having a single female keynote speaker. What message is this sending to young women looking to get involved in the technology field?

With so few women in positions of power in tech it makes it hard for a female engineer just starting out in the industry to envisage a time later in her career where she is running her own department.

If I was to ask one of the male computer science students at Melbourne University who they would want to model their career on, the names Mark Zuckerberg, Evan Spiegel and Satya Nadella would undoubtedly and quickly be uttered. For a female student, this question would pose a little more difficulty if they were to follow in the footsteps of a prominent women in Technology.

Most people would not even recognise the following names:

• Divya Nag - Head of ResearchKit and CareKit Apple

• Michelle Zatlyn – Co Founder Coudflare

• Ginni Rometty - CEO, IBM, US

• Susan Wojcicki – CEO Youtube

Now, it’s not all doom and gloom, for this is slowly changing, with Facebook COO Sheryl Sanberg leading the charge of female technology leaders looking to bring in the next wave of women into the industry.

More needs to be done to increase the number of female leaders in technology – not for sake of optics, but rather to show those girls studying STEM subjects in school your gender isn’t a barrier to you being the next Mark Zuckerberg or Michelle Zatlyn.

So what is next?

For those of us in technology we’ve heard it before, but I’ll reiterate – there is a genuine skills shortage in our industry. Globally, organisations are literally fighting each other for the best engineers, designers and architects.

In relation to women in technology, more needs to be done to not just promote the benefits of a career in technology, but there is a need to highlight the great work being done by women already in the industry.

Of the three issues I’ve highlighted, all can be addressed through a concerted effort by those in the industry to reimagine the way we work and to build a workplace environment free of bias, rewarding and empowering all staff members for the work they complete.

What can you do?

• Encourage as many people as possible to at least look at a career in technology, regardless of their gender, educational background or skillset. Assure them they don’t need to be maths and science geniuses to be successfully in this field.

• Talk to your daughters and the daughters of your friends about IT.

• Ask your schools about the technology curriculum. Ask them what they are doing to encourage an interest in technology related fields - not just maths and science.

• Educate the men within your organisation about bias and discrimination which still exists. Encourage the women in your workplace to speak up about their experiences.

• Talk about the role models which already exists. Actively research who they are and what they have done and promote them within your circle of influence.

• Think about the roles you have. Could they be candidates for job sharing? Could you invest in retraining people who have taken career breaks or are worried their skills are no longer relevant given the pace of change?

• Share articles like this with as many people as you can to promote awareness of the challenges we face within the industry.

Just like they say the cure for cancer could potentially be in the mind of someone with no access to proper education, you could argue the next great technological innovation will be built by a person with no exposure to coding or designing.

And you know what - that person could be a young woman thinking about going to a coding club at your school who just needs a little nudge.

Chris Venter is General Manager, Digital Technology at ANZ

A '404' error occurs when a user attempts to reach a webpage which does not exist. You can try it here: http://acs.com.au/GirlsNotFound.html

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

-

anzcomau:Bluenotes/technology-innovation,anzcomau:Bluenotes/workplace-diversity

IWD2018 LONGREAD: 404 - women not found

2018-02-21

/content/dam/anzcomau/bluenotes/images/articles/2018/February/Venter404_banner.jpg

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

As we celebrate Auckland Pride, we chat to an ANZ staff member about how important it is to have support at work.

12 February 2018 -

Few would argue against more young girls studying STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) subjects. Statistics show employment in the sector is dominated by men at all levels, from education to boardrooms.

11 May 2016