-

Australian investors had a little-appreciated coming-out party just over a year ago when they decided for the first time to put more of their money into South East Asia than New Zealand.

" Outbound investment will be an increasingly important pillar in [Australia’s] economic growth."

Stephen Martin, CEDA chief executiveIt is perhaps not surprising in a country which has long been dependent on a net inflow of foreign investment a watershed event like this would be overshadowed by familiar debates over whether Chinese investors are driving up house prices or whether an Indian investment in coal should be subsidised by the government.

When it comes to the most challenging ‘sticky’ offshore investment – direct ownership of hard assets and people on the ground or foreign direct investment (FDI) - the Kiwi option still prevails.

Australian FDI in New Zealand continued to exceed South East Asia by $A60.5 billion to $A37.7 billion in 2015.

Nevertheless, the fact total investment (including portfolio shares and other financial transactions) in our closest Asian neighbours topped New Zealand by $A100.7 billion to $A98.7 billion suggests a change in orientation is finally under way.

Slowly pushing

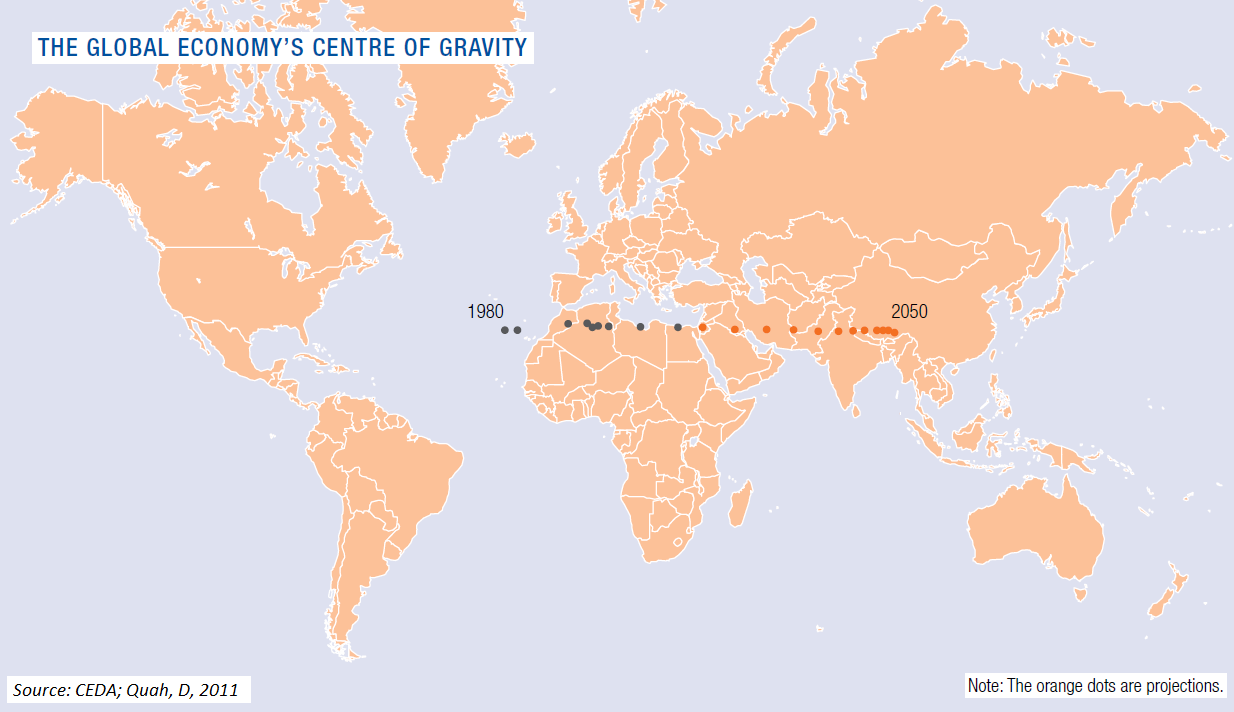

Although the debates about foreign investment into Australia from the British control of vast swathes of farmland in the 1800s to the Chinese inflow today grab the most attention, Australian investment abroad is growing and slowly pushing into new countries and industries. And a series of new studies have shed fresh light on how this is happening.

Last year’s Australia’s International Business Survey (AIBS) by Austrade and the Export Council of Australia identified for the first time how China is now the prime target for overseas investment but closely followed by the US and Britain.

More significantly - given the debate about exporting jobs - the survey showed accessing new markets and building brands outside Australia outweighed cutting costs as a reason for going offshore.

Recently another study by the Perth USAsia Center of Australian economic links with the US revealed the striking fact US product sales by subsidiaries of Australian companies in the US now quadruple the value of direct exports to the US underlining the potential reach of FDI.

Now the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) has released a study and series of essays which aim to raise the awareness of how foreign investment brings expertise back to Australia and builds on the benefits of exporting.

“Australia’s outbound investment and its economic benefits have received considerably less attention than inbound investment as the latter is often emotive and couched in concerns about ‘selling the farm’ or national security,” CEDA chief executive Stephen Martin says about the publication Outbound Investment released this week.

“However, outbound investment will be an increasingly important pillar in our economic growth.”

Manyfold

Echoing the AIBS survey, the CEDA report argues the benefits of outbound investment are "…manyfold and go beyond cost savings; benefits range from exposure and access to new international markets, information and contacts, an improvement in competition (including domestic competition), higher integration in the global value chains and ultimately, the flow on effects in Australia on the labour market (including in the creation of highly skilled jobs) and economic growth.”

Some of the key recommendations are:

- The federal government should use its forthcoming white paper on new foreign policy directions to clearly define the benefits of foreign investment out of the country;

- Australian business should focus more on investment in Asia rather than rely on being a traditional bulk commodity seller;

- Those businesses should take better advantage of existing human capital in the form of migrants and Australians living in Asia to develop an offshore presence;

- The Export Finance Insurance Corporation should refocus its activities on small and medium enterprises which are newly exporting to Asia, especially in the professional services area;

- The Productivity Commission should examine whether the current dividend imputation system acts as a constraint on outward investment because foreign taxes are not subject to dividend franking; and

- The agriculture and food industries should create food processing and innovation clusters in Australia to better integrate their products into supply chains into Asia.

A key part of this process would be to use Australia expertise to develop better chilled food distribution systems in the region.

{CF_IMAGE}

While Australians had a stock of $A2.1 trillion in offshore investment in 2015 (compared with a total stock of foreign investment in Australia of $A3 trillion), the CEDA report is focused on the long term FDI rather than short term portfolio investment. This was $A542.6 billion in 2015 which was unusually down slightly for the first time in several years.

The US (with 19.4 per cent), Britain (15 per cent) and New Zealand (11.2 per cent) dominate this investment reflecting the way many businesses are more comfortable investing in similar political and economic cultures abroad.

But these shares have fallen significantly over the past decade (especially for the US from 40 per cent in 2005) with the percentage shares for China and South East Asia rising although not as fast as the US decline.

“Despite the growth of outbound investment to Asia, it is still underweight given the nation’s export flows,” CEDA economists Sarah-Jane Derby and Nathan Taylor argue. “Australia’s history with manufacturing may, at least partially.”

PwC partner Andrew Parker writes the end of the mining boom means Australia must look for new means to drive growth.

“The good news for Australia is that we are rebalancing growth back towards a greater reliance on our service sector at the same time as Asian countries, most notably China, are increasing consumption as the middle-class consumer population expands,” he says.

“But if Australia is to participate in the growing Asian consumer economy as more than just a farm, a quarry or a beach, we are going to have to engage and invest more in Asia’s markets and businesses.”

Distribution

Parker argues Australia’s overall outward level of FDI is about the same proportion of GDP as the average for major economies around the world but the distribution is wrong.

Only a bit more than 10 per cent of Australian FDI goes to Asia compared with about two thirds of exports raising the question of whether Australia can sustain its export performance when services are growing in importance without greater investment.

But finding the right benchmark for the appropriate level of direct investment into fast growing Asia is more complex than simply using the benchmark of export success. The right benchmark is very much in the eye of the beholder.

For example, Australia’s proportion of FDI going into Asia seems to be about the same as the proportion of US and British investment going to the region.

Australia should arguably have a larger share because it is so geographically close to Asia but on the other hand companies from the US and Britain have been investing into Asia since before Australia became a country.

Another way of considering this conundrum (detailed here) is to look at how about seven per cent of Australia’s FDI now goes to South East Asia which is more than a 300 per cent increase over the past decade.

That may seem small based on proximity but it is more than double the proportion of US investment in Mexico despite the US having a 23-year old trade agreement with Mexico and a shifting border during its early history.

Japan provides the counter example for Australia with about 30 per cent of its FDI in Asia (including a large chunk in China despite diplomatic tensions) or 35 per cent if Australia is included in Japan’s version of Asia. This is more than what Japan has in the US.

New ideas

The CEDA study particularly highlights food processing and agriculture as industries where Australia needs to develop a new investment strategy for sustaining and building a growing export opportunity.

“The case for new, outbound investment is stronger for Australian exporters of high-value agricultural and processed goods, such as premium-quality food and beverages, and in services delivered into Asian markets,” former trade minister Craig Emerson says.

“Offshoring of manufacturing and back-office services is becoming less important, as the impact of relative wage costs on locational decisions declines in the Digital Age.”

University of Southern Queensland agriculture value chain expert Alice Woodhead says the “country or companies that will gain the most market share in Asia will do a lot more than sell food to importers at a food fair.”

“For Australian companies to compete in these markets there needs to be deeper engagement in Asian business that includes managing, partnering or investing in food distribution infrastructure and services,” she says.

“Finding better ways to connect Australia’s natural product advantages and expertise with emerging global businesses in Asia will be critical to future contribution of the agrifood sector to economic growth.”

Greg Earl is an editor and writer. He co-authored the CEDA report essay Integrating Australian agriculture with global value chains with Professor Alice Woodhead and Dr Shane Zhang.

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

To hedge oil or not to hedge oil is the big question. Rising volatility accentuated by uncertainty on whether there will be an oversupply or shortage of oil is causing many a dilemma to companies for whom oil is a significant input cost.

3 April 2017 -

Judging by the headlines of McKinsey & Co’s latest Asia-Pacific Banking Review, it’s becoming less attractive to bank in the region as an era when this part of the world was the most fertile for growth loses vigour.

20 April 2017 -

Demonetisation has been the buzzword of India since the bulk of the country’s cash was removed from the economy at short notice. For many it was a shock to the system, with their economic lives grinding to a halt as the cash shortage disrupted their ability to pay, and also be paid.

3 April 2017