-

For a central banker, Andy Haldane is a Shakespearean fool – not that he’s foolish, in fact exactly the opposite. Under the guise of speeches with titles like The Dog and the Frisbee he cuts through the pomp of the regulatory court with incisive and often irreverent – and sometimes perplexing – wit.

" Organisations can’t demand trust; they must demonstrate not preach their purpose; they have to speak a language the public understands – and they have to listen."

Andrew Cornell, Managing EditorTake his latest work: nearly 12,000 words, 16 charts, 2 tables and 6 pages of footnotes - on simplicity. At least it lives up to its title: A Little More Conversation, A Little Less Action. (And there are Elvis references.)

Sparkling in its own right, the speech is a must read for corporate executives and communicators in this era. He cites Charles Dickens, properly: “Depending on who you follow on Twitter, for central banks it is the best of times and the worst of times; it is an age of wisdom and an age of foolishness; it is an epoch of belief and an epoch of incredulity.”

Ostensibly an argument for more and more comprehensible central bank communication, this speech is also the most rigorous argument I’ve seen around the importance of trust, purpose and transparency in the modern, fragmented media landscape – which he also does a superb job of analysing. It’s also a must read for corporate leaders bewildered no one believes what they say.

In a conclusion worthy of Jacques Derrida, Haldane accepts it “is an irony, and not one lost on me, that this speech is a classic example of one-way central bank communications”.

“Worse still, it comes in at around 11,500 words, contains 2,000 adverbs and adjectives and has a reading grade score of around 11,” he adds. “Perhaps central bankers, like this one, have always been better at preaching than practicing. If so, that needs to change.”

Inexplicably, Haldane doesn’t reference former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan’s definitive example of central bankspeak: “I know you think you understand what you thought I said but I'm not sure you realise that what you heard is not what I meant”.

But there are no shortage of pithy examples of the uber-arrogance of central bankers from eras of genuine corporate arrogance.

{CF_IMAGE}

On the Bank of England’s early years: “The prevailing ethos was well-captured by the job description provided to the official who became, in effect, the Bank’s first press officer: ‘keep the Bank out of the press and the press out of the Bank’”.

When pressed by a Parliamentary Committee in 1930 to explain the Bank of England’s actions, then governor Montagu Norman replied: “Reasons, Mr Chairman? I don’t have reasons, I have instincts”. Haldane notes “building trust and legitimacy is among the most pressing issues facing central banks today,” he says – but it’s not just central banks.

His next point summarises the phenomenon that is at the heart of every communications conference, every corporate purpose discussion, every consultancy pitch, of pretty much the last decade: “Where once trust was anonymised, institutionalised and centralised, today it is increasingly personalised, socialised and distributed.”

The challenge Haldane notes “is to rebuild trust among a wider set of societal stakeholders, more distrustful and diffuse than ever previously, using a set of trust-building technologies, less well-understood than those used previously”.

“Those new frontiers include communicating in simpler, narrative language that engages a wider audience using localised, personalised messaging; finding new ways to engage with cohorts of society currently out of reach, listening as often as talking; and using new technologies – nudging and polling, naming and gaming – to better understand the views and behaviours of wider society. For central banks, this is a brave new world.”

They’re not alone on Prospero’s island.

Haldane itemises the communication revolution at the BoE: “A century ago, the Bank issued one speech a year. In 2016 alone, it issued 80 speeches, 62 working papers, close to 200 consultation documents, just under 100 blogs and over 100 statistical releases - in total, over 600 publications. And this revolution has taken place, in central bank terms, at warp speed.”

He could further point out these are not distinct items. Good communication means using multiple platforms, targeting diverse audiences, with translations – whether into Twitter or podcasts – of the same content. It’s a mistake to think this channel requires only this kind of content or that content fits certain pillars or doesn’t benefit from being amplified over multiple platforms.

It has ever been thus, actually. Haldane draws attention to body language: “In the 1920s, the Governor’s “eyebrows” famously became one of the Bank’s means of communicating. The eyebrows were, in a way, a primitive form of emoji: sterling crisis – sad face. Nonetheless, for even the most malleable-faced Governor, the ‘eyebrows’ were an imperfect communications medium.”

Imperfect, yes, but as a video adds flesh to the bones of written text, they added a richness of meaning.

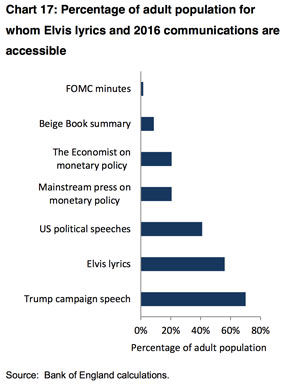

Haldane does an excellent job of analysing the complexity of central bank speak, again using rigorous analytics, comparing the complexity of the US Fed’s Federal Open Markets Committee utterances with Elvis Presley lyrics. He prefers Elvis.

He concentrates on complexity but could have attacked jargon, equally culpable in excluding the understanding of a broader readership while suggesting a lack of credibility in the user – although maybe this is best left to the incomparable Lucy Kellaway from the Financial Times.

Haldane’s most important argument though is around dwindling trust. “It reflects a widening gap between trust in institutions among the elites (which has held firm) and among the general public (where it has fallen),” says. “This trust gap between elites and the general public averages 15 percentage points globally, having been around 9 percentage points as recently as 2012. In the UK and US, this gap is around 20 percentage points.”

Part of that dwindling he attributes to recent history, part to modern media, part to a habit of broadcasting by institutions rather than listening.

“Claude Shannon, the grandfather of information theory, did not define information by words or digits,” he notes. “Instead he defined it by whether uncertainty was reduced on the part of the receiver. If receivers are overwhelmed by the depth, discouraged by the density and bamboozled by the complexity, reporting can be disinformation on Shannon’s criterion. For a chunk of society, the very volume of reporting may be increasing uncertainty and impairing information, understanding and trust.”

Haldane is no Luddite or nostalgist. He urges central banks to use modern platforms, listen to the public, using gamification – in short, actually communicate.

The lesson is clear in this climate of information which is personalised, socialised and distributed: organisations can’t demand trust; they must demonstrate not preach their purpose; they have to speak a language the public understands – and they have to listen.

{CF_IMAGE}

Andrew Cornell is managing editor at BlueNotes

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Fostering the right culture, nurturing talent inside the organisation and investing in employee engagement are fundamental to the success of modern organisations, ANZ’s newly-appointed Group Executive, Talent & Culture says.

2017-04-04 11:59 -

Does business exist just to make money or is there a role for enlightened self-interest and helping communities work?

2017-04-11 08:26 -

Emotional intelligence - the ability to identify your own emotions and those of others - is now regarded as a core skill for leaders who want to get the best out of their teams.

2017-04-10 08:13