-

Climate change is now widely recognised as presenting potential financial risk. Investors and other financial agents must decide exactly how they respond and take advantage of the opportunities which might arise.

" We applaud the acknowledgement climate risk should be measured and disclosed. But what do these disclosures tell us?"

Kate Mackenzie, Manager, Investment & Governance, The Climate InstituteIn contrast to some of the other broad changes under way, such as technological disruption and geopolitical shifts, there is a reasonable amount of empirical information about how climate change might affect investors and other financial agents.

However, taking a position is not possible if you don’t know what the exposure is. For this reason, financial institutions are increasingly being asked by shareholders to measure and disclose their exposure to carbon risk.

ANZ’S CARBON RISK

ANZ commissioned my organisation, The Climate Institute, to comment on its new carbon risk disclosures, released with its interim results on May 3.

We applaud the acknowledgement that climate risk should be measured and disclosed. But what do these disclosures tell us?

With respect to ANZ’s financed emissions disclosure, counting up the amount of greenhouse gas emissions ‘financed’ by a bank or other financial institution is a fraught and complex exercise. There have been attempts by industry-backed initiatives, third-party analysts and NGOs. Banks are complex.

However the big Australian banks are relatively simple creatures. Mortgages make up the majority of their loan books, along with the usual asset management, retail financial advice, insurance and superannuation.

Yet it’s clearly not straightforward to measure the financed emissions arising from being the lead arranger of a syndicated loan or underwriting a debt issue for a diversified company.

PRINCIPLES OF DISCLOSURE

Some basic principles for disclosure would start with a robust and transparent methodology. They would also require metrics that can be compared - both to industry peers and to one’s own previous and future performance. This both recognises shortcomings and potentially provides an incentive to continually improve

However, companies and institutions should be wary of being exclusively focused on relative performance or improvement. Ultimately it is the absolute amount of emissions that matter.

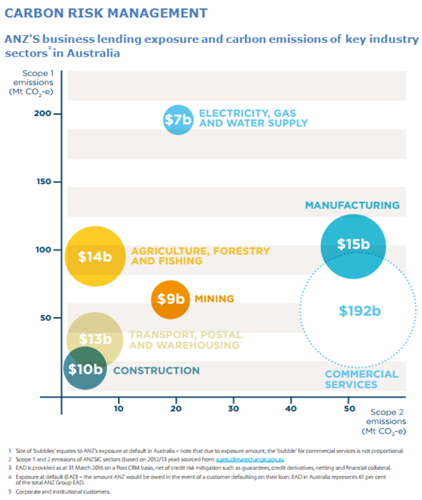

Mapping out scope 1 and 2 emissions from each sector, as ANZ does in its announcement, is a reminder some sectors are much bigger emitters than we might think. The total emissions from the commercial services sector, for example, are much larger than from mining or construction.

However, none of this data on emissions intensity by sector is specific to ANZ. It is derived from NGER (National Greenhouse Energy Reporting Act 2007) data - that is, it uses average scope 1 and 2 emissions from the sector, rather than the amount specifically financed by ANZ. This means there is no scope for ANZ to demonstrate it has improved in future years.

The emissions intensity data is not specific to ANZ, making the data points of limited use. How would it spur ANZ to reduce its carbon exposure? For example, “Commercial Services” lending appears to comprise ANZ’s biggest single sector of carbon exposure but clearly it would be self-defeating to curtail lending to this entire sector.

More useful would be to have emissions by sector specific to ANZ’s own loan book. That would allow the bank to measure any tangible progress in reducing the emissions it directly finances. This could include requiring emissions disclosure when new lending or refinancing is being sought.

Next, the emissions intensity data is of limited usefulness when comparing with other banks. Comparability to peers is important.

ESSENCE OF DE-CARBONISATION

TCI doesn’t believe fossil fuel extraction is the beginning and end of decarbonising the financial chain. Demand factors (emissions prices, energy efficiency, transport) matter, as does substitutability (for example, it is particularly difficult to decarbonise air travel in the short-term).

Metallurgical coal will be necessary to build new energy and transport infrastructure. However the fossil fuel industry is ‘special’ in that extraction and production investments are generally large and long-term – and therefore can lock in future consumption. That consumption results in emissions accumulating in the atmosphere, regardless of how cheaply or expensively it is combusted.

It’s true like-for-like comparisons are not necessarily fair and in the complicated realm of financed emissions and climate risk, perfectly comparable data is not always even possible.

The big four Australian banks specifically disclose financing of the resources sector’ including breaking down the sector into coal, oil and gas, iron ore, and other categories. This is potentially quite a useful means for comparison.

However these are calculated in one method (Exposure at Default) by some banks and another (Total Committed Exposure) by others. The two methodologies reflect group-wide reporting practices, so are difficult to correct.

ANZ notes it is responding to the work of the global Financial Stability Board which set up a taskforce in December to produce a framework for comparable climate-related financial risk disclosure.

The taskforce has identified its scope and established disclosure principles but the framework won’t be finalised before late 2016.

WHERE NEXT FOR DISCLOSURE?

In the absence of a universally agreed and standardised methodology, what should and could banks be doing? It’s worth noting the banks themselves have committed to working on a standardised and comparable approach.

Commitments were made in late 2014 to deliver financed emissions reporting and to construct an Australian pilot project to develop a methodology as part of a global initiative on financed emissions.

Last November, the big four banks quietly announced the Australian Portfolio Carbon Group, an informal working group recognised by the UN’s Environmental Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI), to enable measurement and disclosure of climate performance and demonstrate how they will support the transition to a lower-carbon economy.

The rationale is “financed emissions” is not a sufficiently useful metric, either in terms of pure risk or in terms of contributing to meeting the 1.5-2C goals.

This makes sense and we look forward to hearing more about their work; so far the pace of work towards a disclosure framework for Australian banks has been disappointingly slow.

We recognise it can be difficult to be a ‘first mover’ if that means foregoing business to competitors but that is why industry initiatives are so important - as is actively advocating for industry rules and guidelines that support all participants to reduce their climate risk while allowing flexibility in how to achieve that.

WHAT COULD ANZ DO?

There is an opportunity for leadership. ANZ could:

• Adopt the most stringent policies possible for future financing. Several US and European banks (including Credit Agricole, Goldman Sachs, and JP Morgan) have declared they will not finance new coal-fired power capacity in developed countries unless carbon capture and storage is deployed.

• Australian banks could at least make this gesture, as in Australia even electricity generators acknowledge the future trajectory for coal-fired power is to close existing plants. A more meaningful approach would be to rule out re-financing existing conventional coal-fired plants.

• Encourage and support innovative ways to reduce emissions throughout the economy. For example, banks, as the biggest providers of residential development finance, could incentivise the construction of more energy efficient buildings - thus helping reduce one of the biggest sources of emissions.

ANZ’s 2016 Corporate Sustainability Update mentions agricultural sector emissions will remain high until more sustainable forms of farming are adopted but is it explicitly supporting this type of farming via its lending decisions?

• Explicitly measure and disclose climate-related risk along with other risks. ANZ discloses in its Annual Report it has significant exposure to the resources sector, which could be affected if commodities prices fall (which, by the way, they have).

• Measure and disclose risks from and exposure to the physical impacts of climate change. This is clearly in the interests of shareholders and is increasingly technologically feasible.

• Tally up losses which arise from high climate risk sources. ANZ in March said its write-downs would be $A100 million higher than forecast just a few weeks earlier, due to losses arising from the resources sector. Peabody Energy was identified as one source of losses by Bloomberg News.

Informing investors of how much of that came from thermal coal and other high-emissions sources would illustrate correlation or overlap between material risks and carbon risks, without needing to prove the extent to which climate was a factor.

• Comprehensively report against previous commitments. ANZ pledged last year to “fund and facilitate at least $A10 billion by 2020 to support our customers to transition to a low carbon economy, including increased energy efficiency in industry, low emissions transport”. Granular reporting against this commendable goal will encourage peers to do the same.

Kate Mackenzie is Manager, Investment & Governance at The Climate Institute

SENSIBLE CHOICE

How can an investor make any sensible choice about a financial institution’s management of its carbon risks? Unfortunately, the current 400 plus benchmarks, indices and reporting frameworks which aim to inform the market haven’t really achieved that goal.

That’s one reason why you could almost hear a collective sigh of relief when the Financial Stability Board – under the auspices of the global bank regulators - announced last year it would seek to develop recommendations for voluntary carbon risk disclosures which are consistent and useful.

Disclosure of carbon risks will play an increasingly important role in enabling stakeholders to determine both the level of risk to which a company is exposed and its ability to manage those risks.

For reporting to be useful disclosure frameworks must generate comparable and consistent reporting. Within Australia alone there are numerous overlapping frameworks and a range of disclosures being made.

While this highlights how individual financial institutions are thinking about and managing risks, there’s no relatively quick or easy way to analyse and compare domestic banks with each other or overseas banks.

ANZ has taken some small steps, including:

• Reporting on our own operational carbon footprint and directly financed emissions for power generation, the single largest source of Australian carbon emissions

• Disclosing business lending exposure to the carbon intensive energy, mining, and manufacturing sectors, as well as commercial services and agriculture

• Explaining how we factor these sectors’ carbon risks into our lending decisions and how we’re working with customers to support their efforts to reduce emissions.

We use a range of research and analytics, together with customer engagement, to identify, assess, review and monitor carbon risks.

We’re conscious our customers, big and small, could be impacted by the physical effects of climate change (through extreme weather events) as well as changes to laws, policies or regulations.

By talking with our customers and analysing publicly available information (including their own existing disclosures) we assess and factor these risks into our customer evaluations and lending due diligence.

DUE DILIGENCE

We are also strengthening our due diligence processes for the financing of any new or existing coal mines, the transport of coal, and financing of coal fired power generation. This includes reviewing customers’ efforts to reduce their emissions. We will not fund ‘conventional coal-fired power plants’ that do not use commercially proven technologies to significantly reduce carbon emissions to at least 0.8 tonnes per megawatt hour.

We encourage the efforts by our customers to increase transparency including, for example:

• Publicly reporting the actions they are taking to invest in energy efficiency and lower-carbon manufacturing processes, power generation or transport

• For our larger and most carbon risk exposed customers, publishing their resilience to future policy scenarios, eg ‘stress tests’ of their business against a range of possible policy scenariosand disclosing whether they use a forecast of future carbon pricing or other mechanisms that feed into capital expenditure decisions (BHP Billiton is a clear leader here).

• Maintaining the ability to diversify their business to invest in more efficient resource use and less emissions-intensive products or processes. And, if they are unable to diversify, what is the possible cost of future regulation on their business model.

It will be the efforts of our customers and others to improve their energy efficiency that will make a significant difference, including better insulation, advanced heating and cooling systems and energy efficient devices like LEDs.

Energy production currently accounts for two-thirds of the world's greenhouse gas emissions, so moving towards lower emissions energy generation over time is also critical. The transition will also involve a mix of energy fuel sources - renewables, gas and coal.

In short, much of the information provided by large carbon emitters demonstrates efforts to increase transparency and manage climate-change risks – and how we are supporting them to do that - is already available. But its disaggregated, often largely in ‘tech’ speak and not directly comparable.

That’s why we are all hoping the FSB will give at least the advanced economies and their banks a new set of rules, which will enable investors to understand what the banks - and their customers - are doing to identify and manage their carbon risks.

Kevin Corbally is Head of Credit and Capital Management at ANZ Institutional

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

This story is an edited version of a workshop delivered by Katharine and Catherine at the ANZ Global Capital Markets Corporate Debt Conference in 2016.

23 March 2016 -

It was once as regular as the annual corporate Festive season card. Some drunk employee would photocopy part of their anatomy, proposition a colleague or abuse the boss at the end-of-year knees up and word would gradually filter out about the ugly yet familiar aftermath.

8 January 2016 -

From Lance Armstrong to Executives at FIFA and the International Olympic Committee, the modern sporting world has been rocked by stories of corruption. But according to research from PwC the problem is more widespread than sport - and rising quickly.

4 January 2016