-

"Investors and politicians alike are responding to the increasing need for action on climate change."

Sally Adee, Editor, GameChangersInvestors and politicians alike are responding to the an increasing need for action on climate change by making explicit fossil fuel costs, which have long been obscured and in the process kept artificially cheap.

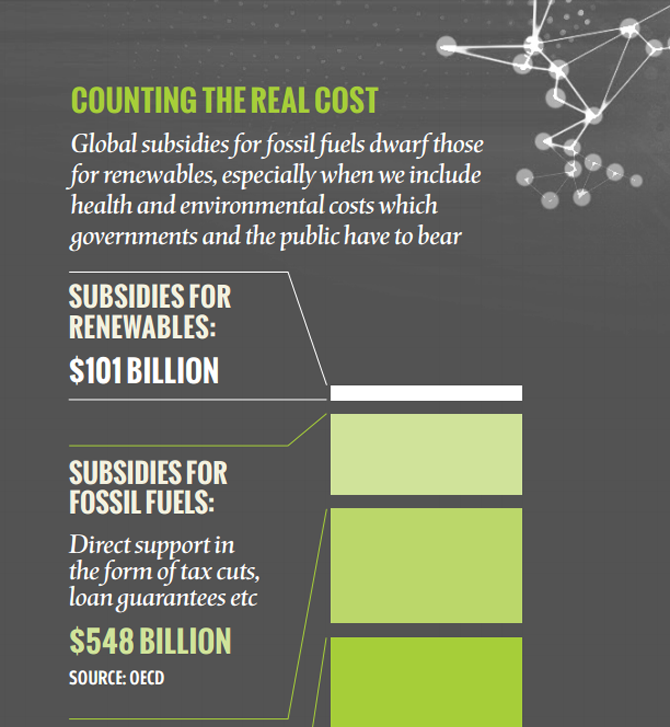

This is in turn leading to major scrutiny of longstanding fossil fuel subsidies to both the mining industries and consumers of their product. Conservative estimates put the subsidies at roughly $US500 billion a year worldwide – over four times as much as global subsidies for renewable energy.

A recent analysis from the International Monetary Fund, which factored in a wider range of supports, such as state subsidies of healthcare costs linked with pollution from burning fossil fuels, arrived at a figure more than 10 times that: $US5.4 trillion.

{CF_IMAGE}

{CF_IMAGE}

That’s a lot of money politicians can spend elsewhere, and some are doing so: Germany is on track to end coal subsidies by 2018, for example, while other countries cutting back broadly include Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

There is still plenty of resistance. US Congress has ignored US President Barack Obama’s annual calls to eliminate $US4 billion in oil and gas sector tax incentives.

Fossil energy suppliers will “hang on tool and nail to every last subsidy”, says Susan Reid, vice-president for energy and climate at Ceres, a Boston-based non-profit focused on sustainable investing.

However, she says the logic behind cutting subsidies is “unassailable”, noting even the CEO of Enel – one of the world’s biggest electric utilities, based in Rome, Italy – recently called for their elimination.

Indeed, Reid expects the pendulum to swing all the way from fuel subsidies to carbon pricing. By 2020, she says, a “critical mass” of the world’s leading economies will be putting a price on carbon, forcing fossil fuel producers to internalise some of their products’ healthcare and ecosystem costs.

The Canadian province of British Columbia charges a $C30 ($US21) fee per tonne of carbon in fuels, for example; neighbouring Alberta plans to impose a similar carbon tax by 2018. Others are developing carbon markets rather than taxes: ‘cap-and-trade’ schemes that make industries acquire tradable carbon credits in order to legally pump CO2 into the atmosphere.

China has piloted seven such markets in major centres such as Shanghai, Tianjin and Shenzhen since 2013 and plans to have a national market in place by 2018.

Industries can take a similar approach: the global aviation industry, for example, is set to operate such a market by 2020.

This transition will not be easy. Europe’s groundbreaking carbon market experienced serious teething problems with member states issuing too many credits, thus undercutting the price of emissions.

Next-generation markets, such as one shared by California and Quebec, include features aimed at making them more effective: for example, a floor below which the price of carbon credits cannot fall maintains pressure on polluters.

Sally Adee is technology feature editor at New Scientist

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

When we think 'digital', we often think of beautiful apps and websites containing cutting-edge functionality, delivered via simple user interfaces striving to create a flawless experience and, in doing so, encouraging customers to engage.

29 March 2016 -

One of the interesting discussions sparked by Maile Carnegie's decision to leave Google to join this bank, ANZ, was around whether banks might soon be better run by technologists.

8 March 2016 -

The cult of analytics seems a million miles removed from dirt, but data management is being used to map and categorise soil in the hope it will lead to greater food security, better soil health and long-term benefit to the global agriculture sector.