-

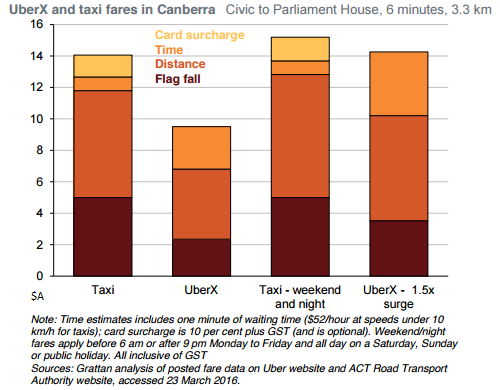

The rise of the sharing economy can save Australians more than $A500 million on taxi bills, help them to put underused property and other assets to work, and increase employment and income for people on the fringe of the job market.

" While the private sector will drive the peer-to-peer economy, government can play an important role to support its growth while reducing any downsides."

Dr Jim Minifie, Productivity Growth Program Director, Grattan instituteA new report from the Grattan Institute, Peer-to-peer pressure: policy for the sharing economy shows the prize for getting this new online economy right is large and governments should not try to slow its growth in order to protect vested interests.

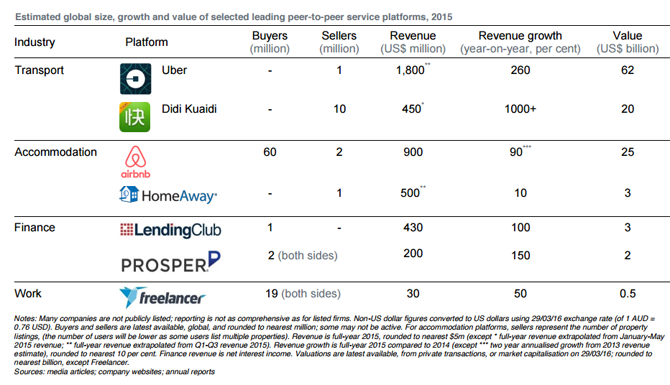

Peer-to-peer platforms such as Airbnb and Uber use online technology to help strangers interact and do business. Platforms host markets in accommodation, travel, art, finance and labour, among other fields.

While the private sector will drive the peer-to-peer economy, government can play an important role to support its growth while reducing any downsides.

{CF_IMAGE}

IMPROVING EXISTING MARKETS

Peer-to-peer platforms use online technology to help strangers interact and do business. If you have booked a holiday rental, a car ride, or even a tradesperson to replace a broken window in recent years you have probably come across them.

Two of the world’s best-known platforms, Airbnb and Uber, enable millions of users to find cheaper and more convenient accommodation and travel. Others host markets in everything from art to freelance work to finance.

They can improve on existing markets and foster new ones by solving the three problems any market faces:

• By bringing together a ‘critical mass’ of sellers and buyers, connecting thousands or millions of participants;

• By making it easy to find a match and establish a price; and x make it safe to do business, by verifying identities, screening suppliers and providing rating and payment systems and even insurance.

• By hosting big markets which are easy to navigate and safe to use, peer-to-peer platforms help people obtain more and cheaper services, and find work that suits them.

Platforms also help people access underused assets, leading some to herald the rise of ‘the sharing economy’. In reality, transactions on platforms are usually on commercial terms. But whether they are used for sharing or commerce, peer-to-peer platforms can increase productivity and incomes.

OBSTRUCTION

Policymakers need to pay attention to peer-to-peer platforms for at least four reasons. First, some regulations obstruct people who want to use platforms, limiting productivity and income growth.

Second, some peer-to-peer platforms can lead to tensions as the market grows. Platforms can also circumvent regulations governments put in place to achieve social goals such as in employment.

Third, peer-to-peer platforms are only the most visible part of a broader shift towards platforms across the economy. Consumer, civil society and business functions – from navigation to communication and finance as well as increasingly sophisticated computing – are increasingly managed on platforms.

Because the value to a platform user may increase as the number of other users increases, a leading platform may acquire a strong competitive position. By the same token, platforms may compete strongly with one another, to the benefit of consumers.

Data access and privacy also become complex challenges when more work is done through online platforms.

Finally, platforms pose tax challenges. By growing the economy and handling payments electronically, they can grow the tax base. But multinationals may not pay much local company tax and smaller peer-to-peer providers may not pay much GST.

FROM ANOTHER ERA

Some say peer-to-peer platforms bring hidden costs by risking work standards, consumer safety and local amenity, and by potentially eroding the tax base.

These worries are not groundless but they should not be used as excuses to retain policies, such as taxi regulation, which were designed for another era and no longer fit.

State and territory governments should follow the lead of New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and others by legalising ride-sharing services such as Uber.

In peer-to-peer accommodation, local councils should allow short-stay rentals run by platforms such as Airbnb, but state governments should give owners’ corporations more power to limit disruptions caused by short-stay letting.

Tens of thousands of Australians are already working on peer-to-peer platforms. These platforms will mostly improve an already flexible labour market, but governments must strengthen rules to prevent employers misclassifying workers as contractors, and bring some platform workers into workers’ compensation schemes. Tax rules must be tightened to ensure platforms based overseas pay enough tax.

Not all traditional industries are happy with the rise of the peer-to-peer economy, but if governments act fast, consumers, workers and even the taxpayer can come out ahead.

Dr Jim Minifie is Productivity Growth Program Director at the Grattan institute

You can read the report Peer-to-peer pressure: policy for the sharing economy here.

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

The Australian government’s newly rolled out innovation and science agenda represents positive political leadership in creating an Australia which values new ideas, business and technology. But it’s wrong to assume innovation is limited to, or synonymous with, fancy new tech.

6 April 2016 -

If you think about your money, there are only so many things you can do, generally speaking – be it earn it, save or spend it, manage it better, borrow it, invest it for the future or, if you’re lucky enough, even give it away.

13 April 2016 -

New technology brings new fears. Will it take jobs from people like me? Can I still provide value in a world driven by machines? Does my company still need people like me?

18 April 2016