-

Banks are leveraged plays on economies because they lend their capital many times over. So when economies are strong, banks perform even more strongly.

" There're major investors punting money on both sides, no shortage of pundits and even a few analysing markets based on Hollywood movies."

Andrew Cornell, Managing Editor BlueNotesIn the current economic climate we are seeing the opposite: global economies remain fragile, despite low interest rates, low oil prices and monetary stimulus. So bank share prices, globally, are taking a hit.

The debate though is whether they have taken too much of a hit or not enough. And there're major investors punting money on both sides, no shortage of pundits and even a few analysing markets based on Hollywood movies.

There's also a conflation of arguments around two separate realms of banking reality: bank system resilience and bank system profitability. While investors – at present – are worried about profitability and dividends others are looking at mid-term bank returns through the prism of whether the system can survive the next crisis.

Obviously the two are interlinked at a certain point in time but the mistake is to make share market investment decisions today, which should be predicated on profitability, by analysing whether banks are too highly leveraged or too thinly capitalised for the next crisis.

One group of investors particularly focused on leverage are debt investors as their concern is whether money leant to banks for three or five years or longer will be repaid in full and whether the interest payments they receive in the meantime properly reflect the risk.

In Australia, disclosure of an increase in bad debts by two banks, this one, ANZ, and Westpac Banking Corp saw bank share prices hit by a factor many times that of the new bad debts. Leverage is biting the other way.

Equity was hit harder than debt and that, in part, is because if a bank does fail, equity investors are the first to do their dough.

As the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the global banking club, notes there is “continued pressure on banks".

“In a challenging economic and regulatory environment, profitability in the financial sector has also been under pressure: weak loan demand, low/negative interest rates and flat yield curves have weighed on margins, as have legacy costs. Despite much-improved capital and liquidity ratios, low bank ROE and market valuation raise concerns," according to the IIF.

But banks are not pure plays on the economy: management and regulation act as dampeners. That is, prudent bank management means not chasing the highest returns available in the good times but not suffering unduly in the bad.

Regulation, particularly since the financial crisis, has focused on restraining banks' excess and in the process limiting the downside as economies slow by increasing capital, liquidity, stable funding ratios and – more challenging – culture.

It's obviously not perfect: banks still manage to blow themselves up and regulators can't foresee or forestall all eventualities.

These attempts to improve the safety of the system come at a cost. There's the direct cost of compliance, the cost of raising capital and the lower return on capital which comes with lower levels of leverage.

There are also other costs. In a recent speech to a seminar in Stockholm, Hiroshi Nakaso, deputy governor of the Bank of Japan, noted there were also costs in low return on capital if that capital couldn't be invested for decent returns – either by lending or in debt markets.

Low demand in the corporate sector means more banks are willing to lend their excess capital at lower rates while low global interest rates make borrowing short and lending longer term less profitable.

The immediate challenge for banks, as the IIF argues, is a lack of demand for lending at a decent price (for banks).

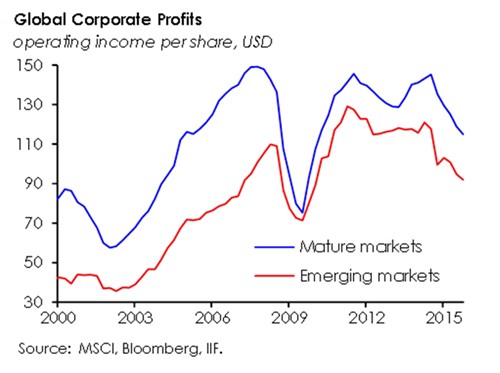

“As we highlight in our new Capital Markets Monitor, the corporate sector is now effectively in a profit recession, both in mature and emerging markets," the IIF says.

“In the US, corporate profits were down 11.5 per cent year on year in Q4 2015—the biggest decline since 2008, and are projected to have declined again in Q1 2016. And despite the European Central Bank's determined efforts to boost the economy … and targeted refinancing (TLTROs) that effectively pay banks to lend to corporates, the situation is little better for the Euro Area.

“The Japanese corporate sector, having enjoyed strong profitability in recent years after the launch of Abenomics, saw a decline in profits in Q4. For the corporate sector in many emerging markets, the trend has been worse: for the aggregate MSCI EM index, earnings have declined on a quarterly basis since mid-2014."

This is a revenue issue for banks. But the fixed cost of regulatory compliance continues to rise, as do funding costs.

For example, in Australia, five year debts costs which reflect the kind of funding global regulators want - to make the system safer - is rising.

“The highlight of last week was the A$2.6 billion, five year note issue by ANZ (rated AA-). The issue is the largest seen this year and only the second with a five year term to maturity from a major bank," the DCM review noted in its April 4 report. “With the introduction of the Net Stable Funding Ratio looming there will no doubt have to be more issuance of this tenor. But as everyone knows it will be expensive and this issue provides ample confirmation of this. “The only other five year issue undertaken (in Australia) by a major bank this year was from the Commonwealth Bank in early January, when it was able to raise funds at 115bps over bank bills/swap. On Thursday, ANZ paid 118bps over, showing that credit spreads are still widening." For context, DCM Review added “we are yet to get back to the February 2012 peak of 185bps for five year funds".

So revenue is anaemic, funding costs are rising, capital requirements are still headed up. And now bad debts are rising.

So are the bank bears right? The answer also depends on context. The bad debt cycle, stretching back five years now, has been very benign. Bad debts charges for failed companies have edged down but added to this has been the added benefit of some bad debts, written off earlier, actually not being as bad as thought – with write backs helping profit.

Actual bad debts are now rising although the impacts are not economy wide – even in Europe. In general they reflect idiosyncratic corporate malaise like Slater and Gordon or Dick Smith's in Australia or particular sectors, notably resources (as commodity prices plunge) and mining services companies and regions (which were hit initially as the resource investment boom wound down and are likely to be hit again if there is widespread failure of mining companies.)

Bears though have plenty of arguments, including, for the Australian banks, looking at the total resources exposure in the context of market capitalisation. This produces a bleak view of the future.

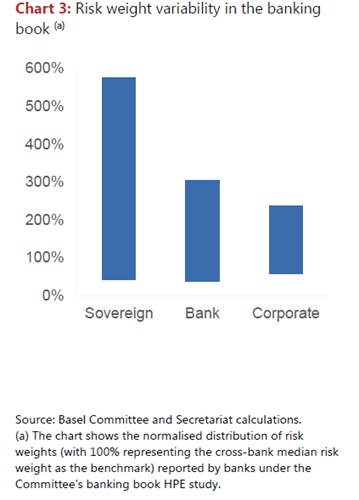

But it also touches on one of the most intense debates in regulation, the concept of “risk weighting" assets.

In the discussion of bank leverage in particular, many – including former Bank of England governor Mervyn King – have argued risk weighting should be ignored. But King argues this because the measurement of risk which goes into the weighting is fraught, inconsistent and prone to delivering banks a number they want.

In a speech today, “The global policy reform agenda: completing the job”, William Coen, Secretary General Basel Committee on Banking Supervision noted “in principle, internal models (by the banks themselves) permit more accurate risk measurement. But, if they are used to set minimum requirements, banks have incentives to underestimate risk.”

What King doesn't argue is loans have different degrees of risk. The challenge is objectively declaring that and so King, and others, reckon the less bad answer is to ignore risk weightings.

That might be simple but it is far from perfect: the biggest name in resources to get into trouble is Peabody with a large asset base linked to coal. But does that mean bank loans to BHP and Rio are just as risky?

In answer to the bears, banks point to the risk in their portfolio, as measured by impaired loans, and the percentage of highly rated – particularly “investment grade" – companies.

Rather than look at particular sectors as a percentage of net assets they say it is more meaningful to look at the proportion of bad and doubtful debts in a portfolio – that is, look at how management deals with risk rather than the risk in the universe.

The critical point is, even if regulators do start to use more simple metrics such as gross leverage, the challenge for investors is actually no less. The attraction of simple measures is also their weakness, simplification.

It will still be up to investors to look in detail at a bank's portfolio, look through to underlying assets, make judgements around how risk is priced and management capability. How indeed risk is “weighted".

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

Over the past few decades technology has changed our lives at an unprecedented rate. For the wealth industry, the convergence of technological and social innovation is pushing us to think and act differently, finding new ways to help people secure their future wellbeing.

2016-03-18 13:23 -

BlueNotes Debates bring together important voices across the business, economic and social spectrum to thrash out where the issues lie. Managing editor Andrew Cornell recently chaired a forum of regional corporate advisory, restructuring and administration professionals. After debating their particular take on the outlook for 2016, the discussion turned to the impact of digital disruption.

2016-04-04 10:13 -

BlueNotes Debates bring together important voices across the business, economic and social spectrum to thrash out where the issues lie. Managing editor Andrew Cornell recently chaired a forum of regional corporate advisory, restructuring and administration professionals to debate their particular take on the outlook for 2016.

2016-02-22 19:04