-

Over the decade to 2013, global investments in the food, beverage and agriculture (FB&A) sectors grew three-fold, topping $US100 billion in 2013. In that time, total return to shareholders of 100 major FB&A companies increased by an average of 17 per cent per annum.

" Food production needs to increase by as much as 51 per cent by 2050 to meet the increasing consumption, on kcal basis."

Michael Whitehead Director, Industry Insights, Agribusiness at ANZThat compares with 13 per cent for energy companies and 10 per cent for IT companies. Yet FB&A doesn't typically leap to mind as a 'hot' sector.

Earlier this century the industry behind what we eat and drink was a staple but maybe a bit stodgy. Then the pace of capital growth really started in the period 2006 to 2008 driven by factors such as US ethanol mandates – the ethanol from corn program dubbed 'food for fuel'.

Starting with corn, soft commodity prices rose. Soybeans followed and there was a realisation a number of soft commodities (rice for example) were at global low stocks-to-use ratios. That in turn led to political responses such as Thailand's ban on rice exports.

FB&A has always been known for volatility and vulnerability to outside factors. Historically that has been weather and often conflict.

Today though we need to be aware the sector will face, if not a Malthusian moment, a significant confluence of global factors driving both demand and supply - all of which point to an inability to feed the world in the way the world wants to eat.

THE BASICS

There is a quandary here: financial returns look promising but governments are increasingly aware of the dangers they face from food security, both in terms of safety and supply. And that will impact markets.

Nevertheless, in recent years, we have seen a growth of major fund activity in the space, the gradual consolidation of assets, which were often inefficient and a rise in commodity prices – even of basics like hay.

THE GLOBAL SUPERMARKET

There is then an inherent tension between the market and food security. The global dimensions of the looming scenario are stark.

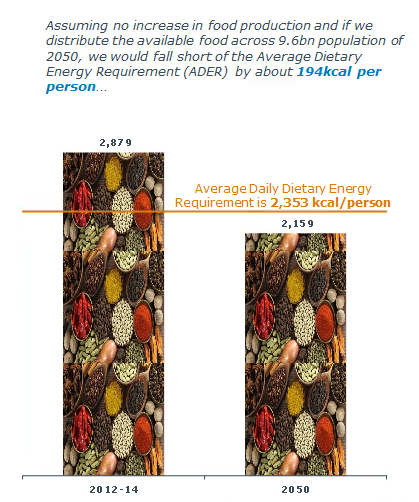

- Assuming no increase in food production and we distribute the available food across 9.6 billion people in 2050, we would fall short of the Average Dietary Energy Requirement (ADER) by about 194kcal per person.

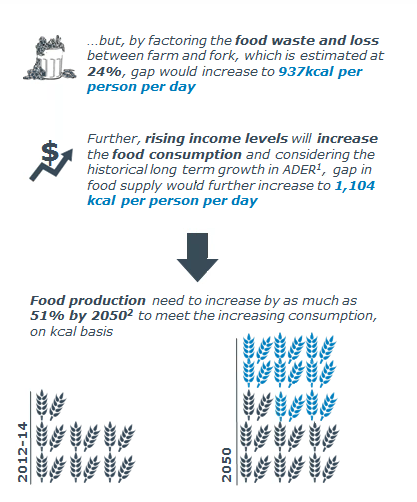

- But if we factor in the food waste and loss between farm and fork, estimated at 24 per cent of production, the gap would increase to 937kcal per person per day.

- Further, rising income levels will increase food consumption and considering the historical long term growth in ADER, the gap in food supply would further increase to 1,104 kcal per person per day.

- Therefore, food production needs to increase by as much as 51 per cent by 2050 to meet the increasing consumption, on kcal basis.

That's before we consider climate change, regulatory, currency and consumer behaviour and, as farmers like to say, “what falls out of the sky".

VIETNAM AND CATTLE

I was recently at a beef and dairy Forum in Hanoi. A key stakeholder from Vietnam said “we get Australian cattle at $A3.50 per unit but we can get Mexican cattle at $A2.50 per unit. You should give us cheaper cattle or we may go to Mexican cattle".

Fair enough, that's how markets work. The Vietnamese clearly want cheaper cattle. But the reality of situation is complex.

In Northern Australia, weather will soon do one of two things:

- Rain a little or not at all. So there will be less cattle going on sale, which will push prices even higher than now.

- Rain enough farmers will hold back their cattle from sale to allow them to breed on new grass.

This reduction of cattle will push prices up even further than they are now.

In that situation, the Vietnamese government and importers and processors will need to seek cheaper product (like Indian buffalo, though there are safety concerns and falling supply) or they will have to pay more. Meanwhile the US, Indonesia, China, and others are sourcing Australian beef.

Adequate and reasonably priced food is vital for Vietnam and other nations such as Indonesia to keep their populations contented. Food security is necessary for stability

WHAT'S THE CHALLENGE?

First and foremost the challenge is productivity. To meet demand we need an increase in efficiency. That in turn should lead to opportunities in products and services such as fertiliser and irrigation.

For example, for Australia to produce 15 billion litres of milk by 2025, up from nine billion today, ANZ calculates an investment of $A8.6 billion is needed. Productivity must be gained from non-productive land.

One of the most egregious and yet surmountable challenges is waste. Nearly a quarter – a quarter – of global food production is simply wasted, for a wide variety of reasons. Consider some of those reasons:

- In developing countries, waste happens at the bottlenecks so that requires improved logistics, trade, processing and infrastructure.

- In developed markets, waste mainly downstream, in retailers, homes.

In both cases, waste improvement is an opportunity. In China, cold storage and transportation are estimated to generate between $US12 and $US18 billion in revenues and are expected to grow 10 to 15 per cent per annum. In developing markets, innovations like extended shelf life and new packaging create opportunities

Itis simple supply and demand: there is a diminishing asset pool in FB&A, particularly in supply chains. In Australia, for example, the number of grain companies has dropped 80 per cent through merger and acquisition.

Demand meanwhile is being driven by a desire by investors to diversify risk – for example, sourcing milk from different markets. Saputo now takes milk for China from Canada and Australia. And investors have high levels of liquidity.

SECURITY

Despite the overarching and fundamental challenge of producing enough calories for growing and wealthier populations, more immediately food security, in its most basic form, is not a challenge for governments. There is not a food shortage. The challenge is to keep populations satisfied with what's available. That means quality and variety.

That political imperative brings governments and state-owned enterprises into the supply chain and they have cheaper capital and greater liquidity. Agri could also be seen as a good place to park foreign exchange reserves as it is a long term play likely to return better than US treasury bonds.

Many SOEs and semi-government enterprises operate under – often opaque – government food security mandates. That in turn brings the danger of protectionism and market restrictions.

While complex, the interaction of these market, technology and political forces is likely to fuel asset prices. Consider the Kidman cattle stations in Australia as a prime example. The price publicly reported was well north of $A350 million, perhaps $A100 million over book value.

As acreage prices climb, farmers can be squeezed out. As regulation grows it can create product shortages. Larger, more complex agribusinesses require specialist management, a challenge especially in developing countries.

Ultimately though the challenge is political, it is not just about facilitating the necessary investment capital but avoiding intervention which distorts markets.

Michael Whitehead is Director, Industry Insights, Agribusiness at ANZ

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

First some bad news: it's getting harder and harder for the world to get the stuff it needs. Food, water and natural resources will all be harder to access over the next few decades and, what's worse, almost everyone will be affected somewhere down the line. The answer? Sustainability.

10 November 2015 -

For all the benefits the Trans-Pacific Partnership will bring to each country involved, a level of consternation has popped up in all countries and in Japan there's been a loud cry from the agricultural sector.

27 October 2015