-

The Financial Times' highly respected Lex column has delivered a slap to (northern hemisphere) bank executives, telling them to stop making promises they never keep.

In a column titled “Bank targets: here we go again”, Lex accused some banks of crying wolf: “Deutsche Bank and Barclays set new targets or tweaked old ones. Last week it was Credit Suisse. Put them all together and there is a bewildering array of objectives to track, especially if you are fool enough to compare them to what the banks had targeted before.”

" In Australia however the ROE target has political dimensions absent from the northern hemisphere."

Andrew CornellManaging EditorBut actually Lex may do bank executives a favour as the column made the point the problem is not targets per se but ones which are hostage to external forces – most notably for banks interest rates and regulation which dramatically shift costs and earnings.

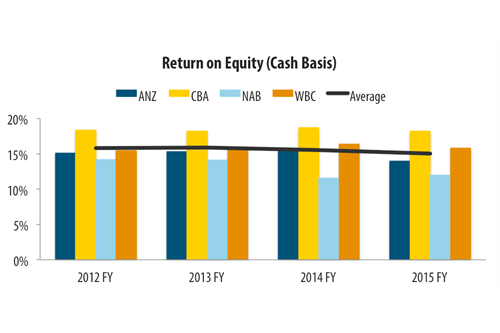

Return on equity is one such target. Superficially it is an attractive bull's eye at which to aim as it tells shareholders what management is aiming to earn on the funds they hand over. Yet, for all management should be held to ROE enhancing decisions on risk, prices, costs or capital allocation, key levers are outside management's control.

{CF_IMAGE}

In the Australian bank reporting season both National Australia Bank's chief executive Andrew Thorburn and ANZ's Mike Smith backed away from ROE targets, citing the uncertainty of regulatory capital requirements. Tidjane Thiam, the new Credit Suisse chief executive, has also refused to set a return on equity target.

In Australia however the ROE target has political dimensions absent from the northern hemisphere.

Lex's complaint was missing targets “has become standard in the European banking industry”.

“Regular target changes suggest a lack of clear thinking internally about what the bank is trying to achieve,” the column opined. “It would be far better to create a simple, short list of objectives on a select few core metrics, stick with them, and not create any more until the first set has been achieved.”

In Australia though the complaint is the ROE targets themselves – and by implication the profitability of the banking sector – are too high.

There's of course an irony in this: many compare the ROEs of Australian banks with European or American banks, the very banks which trashed their earnings during and after the financial crisis and continue to annoy commentators like Lex.

So Australian banks, which performed solidly during the crisis, didn't require taxpayer bail-outs (and actually paid taxpayers for backstop guarantees) now must defend their greater profitability.

The political dimension of this of course is the debate around the price of banking products, particularly standard variable rate mortgages and credit cards. Each price increase – higher interest rates – is compared with what some argue is the too-high ROEs in the industry.

To the extent price rises are reflecting an increase in the cost of doing business – particularly the regulatory cost – the argument is shareholders should pay that cost by way of lower earnings rather than customers.

Yet the debate always focusses upon those to whom banks lend – consumers with mortgages and credit cards. According to the September Australian Prudential Regulation Authority banking statistics, owner-occupied housing loans in Australia stand at $A856 billion with a further $A533 billion lent to investors.

Yet the money lent to Australian banks – their total deposits – stands at $A1.9 trillion. The people who lend to banks include other banks and investment funds but households alone lend $A747 billion – and then there are small businesses, charities and entities like bodies corporate.

Typically, and more so in an ageing society, the rate of return on deposits is a crucial income stream for lenders to banks. The self-managed superannuation fund industry has extensive cash holdings, often invested in simple deposit products.

Yet missing in the debate around who pays for a safer banking system are these depositors. It's rare to see a politician say “let's not forget the depositors who are also impacted if a bank elects to keep mortgage rates lower”. Because one of the dynamics of bank profitability is determined by the margin between what banks borrow at (including from depositors) and lend at (including to mortgage holders).

Underlying all this is the question of just what a bank's return on equity should be. And there is no easy answer because the answer is it should be high enough to compensate an investor for the risk they are taking and compare favourably with other potential investments.

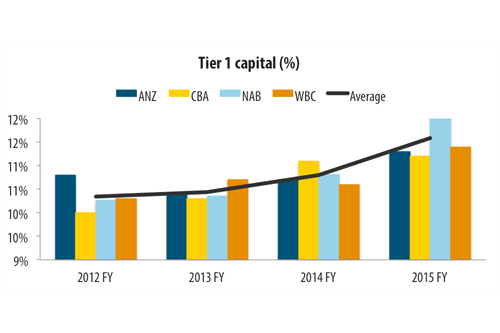

NAB's Thorburn said last week his bank's cost of capital was around 11 per cent so it needs to be higher than that. But what's the appropriate risk premium?

{CF_IMAGE}

I've had some animated discussions in recent weeks with a range of executives, directors, investors, analysts – even regulators - on this theme and it's fair to say there's little agreement.

One school of thought is that with inflation - and hence the risk free rate of government bonds - so low, investors should be prepared to accept commensurately lower ROEs. Moreover, the higher levels of capital now being introduced by regulators should make the financial system safer and hence lower risk.

Yet investors can have longer memories than academics. One investor (and a regulator agreed) said before the financial crisis he would have believed 5 to 8 percentage points was a large enough risk premium for a highly leveraged institution like a bank.

But today, even with banks less highly leveraged, he reckons 10 to 15 percentage points – that is ROEs between 12 and 17 per cent. Westpac Banking Corp this week set a target of 15 per cent.

Much is made of the Miller-Modigliani theory which in essence says the mix of funding of an institution doesn't impact the cost of funding. That is, having more equity and less debt is no different to more debt and less equity.

The reasoning is if there is more debt, the cost of that debt will rise offsetting the cost benefit of less equity. If equity is higher, the cost of debt is lower because the firm is less leveraged.

Reality has proven different. While there is little evidence that higher capital has raised the cost of running a bank, nor is there evidence Miller-Modigliani has happened.

Part of this is other factors – debt, for example, is tax-deductible in many jurisdictions. During the financial crisis, the superior credit ratings of Australian banks didn't help – what mattered to funders was a government guarantee.

These issues are all entwined.

The best answer though to concerns around excess profitability is competition. If regulators and politicians concentrate on lowering barriers to entry and ensuring the competitive field is open, new players will enter if incumbents are making too much money. If they're not making enough, investors will shift somewhere else.

At the moment, consumers are only shifting out of traditional finance institutions at the margin, to “disruptors” like peer-to-peer lenders and direct credit systems. And while Australian bank shares have lost around 20 per cent from the start of the latest regulatory imposts, they are still desirable investments.

The market therefore is saying the balance between customers and shareholders is not unreasonable.

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

-

-

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

The investor-focussed traditional weekend media in Australia did a thorough go over of the implications of the Reserve Bank’s somewhat surprising decisions to cut the overnight cash rate 25 basis points last week.

10 February 2015 -

The tale of the bank profit results and trading updates so far is retail banking is very healthy, business banking promises better but is yet to deliver and the credit cycle, almost incredibly, continues to defy sceptics.

19 August 2014 -

Banks obviously will not escape the current market carnage but over the longer term, and across a range of international indices, they are being sold off more than broader markets.

25 August 2015