-

Fretting about China’s falling economic growth has become an industry. Money managers, hedge fund gurus and business people have amassed years worth of concerned moments.

Meanwhile journalists and online calamitists have fed those fears with millions of words on the topic, exhausting an entire vocabulary of synonyms for crisis.

"While the rate of economic growth has almost halved, the economic power of China has surged."

Jason Murphy, Publisher, Thomas the Think EngineAnd the more China’s economic governors or close watchers implore the west not to worry, the more worrying seems to intensify.

But while China’s headline growth figures have indeed shrunk, the story for the rest of the world has not deteriorated nearly so badly as the catastrophic headlines would suggest.

The reason lies in one of finance’s oldest and most favoured concepts – the magic of compounding.

For while the rate of economic growth has almost halved, the economic power of China has surged.

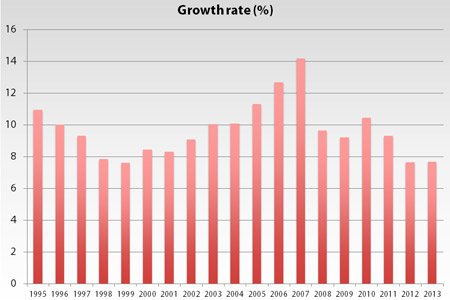

China’s real growth rate peaked in 2007 at an exhilarating 14 per cent, it has since shrivelled into single digits and shows no sign of returning to its peak.

China’s growth in 2012 and 2013 was no better than the growth in 1998 and 1999.

In 1998, China’s economy was a sapling, shooting up but still easily lost in the forest. Now it is among the tallest trees, a towering economic giant.

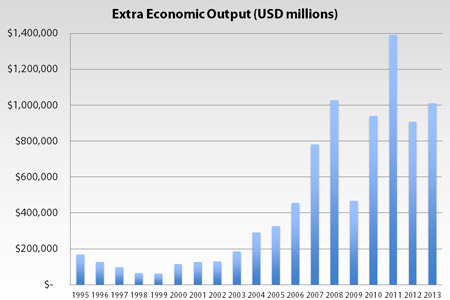

The years of expansion mean that 8 per cent growth now has a very different effect on the size of China’s economy. (Note nominal output includes inflation. Negative inflation in China in 2009 explains a weaker lift in measured output in 2009.)

In 2014 a year of sub-8 per cent growth added one trillion US dollars worth of output to the Chinese economy.

An extra trillion makes a big difference not only to China but also to its trading partners. A trillion US dollars is worth more than half the Australian economy. Each time China expands, so does its capacity to drag the Australian and New Zealand economies along with it.

Big trading partners are vital to economic growth and China has already proved to have a taste for what Australia and New Zealand and indeed its region and the broader world offers.

As Chinese demand for Australia’s iron ore drops off, tourism is rising faster than anybody dared expect. The most recent month for which data exists shows yet another record in inbound traveller numbers.

Putting China’s growth into context helps. In 2013 its economic expansion is equivalent to more than six extra New Zealands. Back in 2003, China’s growth was closer to just one extra New Zealand of economic output.

If China’s taste for Australia and New Zealand’s exports were to remain consistent as as a percentage of China’s GDP then as it grows, China would pass on an ever-increasing bounty of free economic growth.

Even if China fell to 3 per cent growth, it would be adding more economic output than it did in 2006.

The chance of a free ride on China’s increasingly capacious coat-tails is perhaps more obvious to policy makers than to pundits inclined to extrapolate recent falls in Chinese headline growth numbers.

The growing importance of China as a source of growth, not just of risk, is evident in the way it features in Central bank thinking and communications.

“They are by now … the largest trading economy in the world. An economy of that size growing at 7 per cent is still quite an impressive performance, if they can do that,” RBA Governor Glenn Stevens told Parliament in February.

China is now the first foreign country mentioned in most official statements from the RBA and other central banks, getting far more attention than even a couple of years ago.

But of course, the bigger and more important China gets, the bigger the risk. The above optimism applies only so long as Chinese growth remains positive.

If it were to go negative, for some horrible reason related to shadow banking or an over stretched property sector, its increased size and importance to Australia New Zealand and the whole globe would suddenly be a downside. Then we really would have something to worry about.

But that’s not something that is happening now, even if the growth rate is shrinking.

Source for charts: World Bank data.

Jason Murphy publishes the highly popular blog Thomas the Think Engine and is a former writer for The Australian FinanciaL Review.

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

EDITOR'S PICKS

-

China’s emerging affluent youth are online – everywhere and all of the time – there is huge potential for online businesses to take advantage of this growing segment. ChinaSkinny lays out the landscape.

2015-01-07 16:48 -

India is on track to rival China as the largest economy in the world in 2075 in real terms - if it can overcome some key hurdles.

2014-08-08 16:51 -

Dad, Where Are We Going? The answer to that question could be crucial to the economic future of Australia and New Zealand.

2014-12-12 20:22